On Journalism, Democracy, and Design

Also: new projects for the summer.

On a personal note: I tend to overthink my writing and plan out months-long publishing schedules for LETS, which inevitably get overrun by whatever life throws at me. While developing projects here, I’m still a student-researcher at UC Berkeley’s public policy school and occasionally write for Reboot as one of their managing editors.... so while I may not be publishing here as often as I would like to, I’m still constantly thinking and writing for those roles.

Even still, the past six months have given me endless inspiration. I stumbled upon a pragmatic philosophy of democracy that upholds the importance of communities of inquiry. A class project introduced me to the “front porch democracy” of New Orleans’ Ninth Ward. and I have been messing around with the idea of public computing interfaces that build more connection and familiarity on the street. All of this reaffirms my belief that there is something worth pursuing in this idea of civic infrastructure – the spaces, tools, and methods required to collaboratively address our most pressing local issues, and work towards a more equitable society.

So the idea backlog will continue to grow, and I will be urging myself to spill the ink a little more frequently (with hopefully less overthinking than before). Chances are that will look like a monthly update, as that’s just about the limit of what I can consistently publish without sacrificing the quality of my other projects. That said, if you’re interested in helping me publish more articles about how design and technology can be used to fulfill the promise of an equitable democracy, hit me up and I’ll give you something to do.

In the meantime, on to this month’s musings on journalism, democracy, and design:

Journalism’s Role in a Healthy Democracy

I’ve read the news for awhile, but I didn’t think too critically about journalism until the 2016 election. “Fake news” was on everyone’s minds back then, whether as a way for Trump to push back against his opposition or as an explanation for how voters were misinformed on social media. As a technologist, I took a special interest in studying online misinformation, and through that work came to understand the importance of a healthy information ecosystem in a democratic society – and the role that journalists play in preserving it.

I like to think of journalists as applied researchers that seek to spread useful knowledge about topics that impact people’s everyday lives and decisions. Of course, there is a whole ecosystem of people who cultivate knowledge in our society; academic institutions, think-tanks, internal government agencies, and even social media content producers regularly produce and reproduce knowledge that helps everyone else make sense of our complex world. Journalists certainly aren’t required to do the rigorous analytical or evaluative work of other researchers. Instead, good journalists in particular are constantly paying attention to what is happening on the ground in their communities and are able to provide information that is directly relevant to the lived experiences of the people around them. In service of that goal, they should be equipped to synthesize what already exists, augment it with additional research of their own (such as interviews or data analysis), and make it accessible to the masses. This is the thing that I love the most about good journalism: it is intrinsically human-centered.

In this way, journalistic institutions are crucial pillars of a functional democracy. Basically by creed, journalists are obligated to report on things that everyday people actually care about, and provide a common base of information so that everyday people, community-based organizations, and policymakers can to work together to solve problems in their community. Even within a single city, journalism can be seen as necessary adaptation to the complexity and interconnectedness of modern society; it is simply impossible to know everything that is going on around us on our own, and journalists help to build our collective awareness and understanding. In a democratic society, we are able to have conversations about the information that journalists gather, and determine our own perspectives and plans (for more on this, Habermas’ “public sphere” and Fraser’s idea of “counterpublics”).

From a public policy lens, this means that journalism plays a huge role in shaping the policy agenda. Whatever is taking up space in newspapers, social media, and other media actively shapes our perception of reality; for example, if the Chronicle (nonspecific) is repeatedly covering car break-ins, the people who are served by that publication will believe that break-ins are increasingly common and the most important issue of the day. The people who are deeply affected by that issue will be armed with more information and political legitimacy to pressure their elected officials to take action, or to pursue solutions of their own. On the other hand, other issues might get tossed by the wayside based on an outlet’s priorities, such as challenges facing Black people in public housing, issues affecting Latinx immigrants, or the social health challenges facing senior residents. In this way, journalists have the power to shape what we pay attention to and how we perceive those issues, as well as the range of acceptable solutions.

Wherever people are making decisions, journalism even more directly shapes their outcomes. This can have significant effects through formal democratic processes like policy referendums, where everyone has an opportunity to decide whether or not to proceed with a given policy; through this, the information provided through the press and other modes can influence everything from the institution (or elimination) of new city departments to creating new pedestrian promenades. It also has serious implications for the everyday decisions that people must make – whether they’re aware of social support programs that could help them stretch their monthly budget, if they decide to wear a mask in crowded public spaces out of concern for viral spread, or which neighborhoods they believe are safe to visit.

This also means that journalists have a role to play in addressing some of the long-held inequities that undergird this country by giving underrepresented people a voice, shedding light on their issues, and highlighting how the systems around them continually reproduce unjust outcomes. The Black Panthers were known not just by their free breakfast programs (which later inspired state and federal programs), but also through the “The Black Panther” newspaper that reported on Black American issues in both a domestic and international context. Publications like the Marshall Project critically analyze various facets of the U.S. criminal justice system, a system that is particularly tortuous and opaque to the average citizen. This kind of journalism can be used to advocate for social change and draw our attention to root causes of our social ills, rather than convenient symptoms.

Journalism and Design

Those who are familiar with my work know that I believe that it is useful to view public programs as “designed” systems. Whether you’re talking about municipal transportation or public health, all social systems are designed with assumptions about what people need, how they act, and the tradeoffs they are willing to make as a society. As such, they must be redesigned to truly guarantee health, freedom, and safety for all. I think that design should ideally be a practice that is geared towards enhancing life; it requires an acute understanding of social and environmental systems, and seeks to make those systems work better for everyone involved.

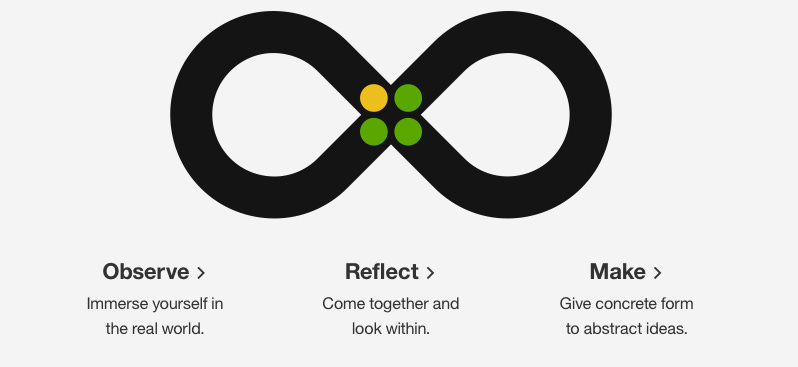

The most basic “human-centered design” education will teach you that there are generally two main spheres of design work: learning and creating. In the learning phase, we build a better understanding of the system at hand and describe the problems we’re trying to address with greater precision. In the building phase, we imagine, build, and test solutions to those problems. This is not always a linear process, nor does it “end” with deployment of some solution; instead, we learn again from what we’ve tried, and develop new approaches from there. While overly simplistic, my favorite representation of this process was developed by IBM’s Human Centered Design team: an infinity loop, where each lobe represents “learning” and “doing”.

Within civil society, I’ve started to think of journalism as the “learning” side of the equation. While journalists don’t often see themselves as design researchers, they are consistently shaping our understanding of the world through their reporting, and thereby shaping how we approach the challenges facing our cities. Many of their methods – such as gathering and synthesizing existing information, interviewing people, walk-alongs, and more – are shared with the methods used by design researchers to learn about systems. When it’s time to develop potential solutions to local problems, designers can then draw from the insights that journalists have uncovered as a starting point for their own research, or as inspiration for the solutions they test.

In an equity-centered practice, the big challenge for designers and journalists alike is to include impacted communities in their processes. Over time, journalists have also recognized that who tells the story makes a difference in the reporting, and the more ambitious of them have started giving more power to the people centered in their reporting. Here in Oakland, I love the work of El Tímpano, which establishes multiple accessible channels for Latinx immigrants to influence what gets investigated and reported on. In Chicago, City Bureau trains people to report on public meetings in their cities and report back to their communities on upcoming policies, the opinions of their elected leaders, and more. The design profession (especially those oriented towards service design, city planning, and other public-serving disciplines) has also begun to make this shift via “participatory design,” in which communities are not only consulted for their opinions but actively engaged in developing and choosing between alternatives. The key in all of these approaches is the power given to impacted communities to tell their own stories and develop their own solutions, with the technical support of professionals.

This is a crucial orientation for those who care about the health of our democracy as well. Advocates of participatory democracy have long advocated for giving everyday residents more power to prioritize what we focus on and shape policy implementation; this both builds greater trust in our governments and hopefully drives resources to where it is most needed. “Collaborative governance” takes these principles and attempts to empower everyday people to participate in the political and administrative processes in an ongoing way, often through community-based coalitions, digital tools that enable more thoughtful participation, or even representative forums like citizens’ assemblies. It’s worth noting that there is a proper science to all of these calls for greater participation; instead of simply assuming that crowdsourcing ideas from residents will solve a problem, practitioners in this space develop nuanced processes to develop sensible solutions.

For me, the real magic happens when these two lobes can come together to create a new ecosystem for understanding and addressing local issues. In the first half of 2023, I supported in the San Francisco Chronicle’s SF Next team, which was an experimental division dedicated to finding practical solutions for the many crises the city faces (from housing and homelessness to public safety and more). I agreed with their assessment that journalists had an opportunity to not only describe problems, but help develop solutions alongside the community. With this in mind, I came up with a strategy for how they could approach this work that drew from theories of participatory design and collaborative governance, as well as my own knowledge of community-based work in the city. And while their team wasn’t able to implement the strategy completely, I still had an opportunity to facilitate a novel discussion on homelessness with people of a variety of lived experiences, and walked away with a much clearer understanding of the problem than I had before. (You can read the strategy I presented here.)

In the meantime, I’m still holding onto this dream. I want to see cities that cultivate a nuanced and holistic understanding of local issues, and work with residents, organizations, and other public actors to improve their communities. This requires cultivating long-term relationships with organizers that have already been engaged in these issues, and can therefore shape the meaning-making process to more accurately reflect reality. Notably, engaging collaboratively does not mean glossing over conflicts in values and interests (as is common in local issues); instead, acknowledging and thoughtfully discussing conflicts can open up new paths, or clarify values that we should hold collectively. Not everything has a simple answer, and political struggle is often still necessary to achieve social change… but journalism and design can work together to support a more engaged citizenry and catalyze innovative approaches to making a better world.

Summer Update

Earlier this year, I was invited to a space in Downtown Oakland that validated some of these dreams around journalism, design, and democracy.

That space is the Oakland Lowdown: a journalism and art studio based in Downtown Oakland. The space (run by Cole Goins and Chris Treggiari) sponsored a program of the New School’s Journalism + Design program, which regularly runs programs to enable more community-centered news, and creates resources on how to practice more systems-oriented journalism. The Lowdown in particular uses their studio space as a physical manifestation of on-the-street journalism; their window displays are used to share resources and preview the art inside, and the indoor space has floor-to-ceiling displays of community perspectives, photojournalism, and more. I was touched to find out that their current exhibit is a collaboration with El Tímpano, featuring portraits of vendors at La Pulga (a longtime Latinx market in Oakland’s Coliseum).

Basically, it’s a third space for civic dialogue – something I’ve always thought was an underappreciated and underrepresented fixture of our civic infrastructure. Even back when I was doing research on misinformation, one of the most important takeaways was that it is much easier for people to discuss their personal experiences when meeting face-to-face. Doing so reinforces the local orientation we share and creates opportunities for richer communication (body language, movement, spatial understanding, etc) in a way that online spaces can never quite mimic.

We’re collaborating this summer to prototype a new model of community-centered design in the City of Oakland, using the ongoing issue of vacant storefronts and sustainable small businesses as an initial subject. Along the way, we’ll be engaging residents, local entrepreneurs, and other stakeholders in conversations that paint a more nuanced picture of the issue from multiple perspectives. As part of this, we’ll also try to work with organizations in the city that have had a long track record of supporting small businesses to understand the issue from their lens. By the end of the summer, we’re hoping to produce an exhibit at the Lowdown’s space at 14th and Harrison that makes the insights from these conversations more useful and tangible for everyday residents and organizers working towards a more equitable, sustainable economy.

This is just the beginning, and there will be plenty more experiments throughout the rest of the year. The most exciting aspect of this for me is the chance to really connect with the people around me; after all, I’ve hardly been in Oakland for a year, and there’s a lot more I have to learn and love about this city. But being able to engage with my neighbors (and to have them engage productively with each other) is what it’s all about for me. With hope, experiments like these open up new opportunities to bring community perspectives into policy conversations, and generally help people of all backgrounds believe that they have something special to contribute to their city.

In any case, I’m optimistic and excited to learn. As always, you can stay in the loop here or on Instagram.

Great observations and synthesis on journalists & designers. I agree there is a lot of overlap and it’s why I felt journalism/research and writing was a natural progression after a long design career. Good to see others make these connections too.

Loved reading this! I often find that national news (and elections) receive most of our already limited attention, but it’s the local news and elections that impact us the most - and journalists possess such a wealth of knowledge and awareness of “all sides” that could be really useful in identifying gaps and improving processes/systems.